A blonde youth, four or five years-old, gazes up from the tableau, a smile on his face. He holds the end of a piece of copper wire. It trails behind him, coiling like a snake. In the background on a shelf, Russian dolls stand in left-to-right ascending height order. Above this, the object on which the boy has cast his vision comes into view — the human object: Peter.

Peter’s head is out of the frame, making him visible only from the neck-down, but on either side of his neck, copper wire curls out, like the styled ends of an absurd mustache sprouting from the face of a hysterically laughing, damsel-tying-to-tracks villain, work boots touching only air as they point to the floor, suspended inches above a stool knocked on its side.

And next to the illustrated frame, titled Don’t Ask Stupid Questions, this verbiage:

I asked Peter the electrician,

“Why is there copper wire around your neck?”

He didn’t respond,

His boots just swayed quietly.

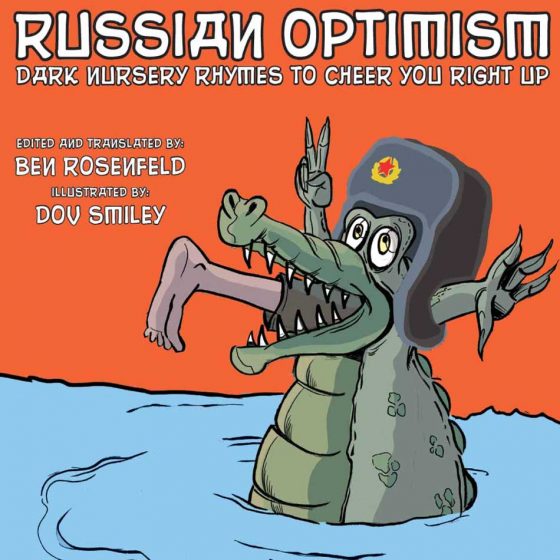

Russian Optimism: Dark Nursery Rhymes To Cheer You Right Up, the brain-child of NYC-based comedian/writer Ben Rosenfeld and graphic artist Dov Smiley, is an illustrated collection of 30 Russian nursery rhymes translated to English, each text snippet set against a graphic-novel style background, bringing it to life with a sinister chuckle. Though the original Russian followed a rhyming form, Rosenfeld made an editorial decision to convey the most accurate meaning in English, eschewing deliberate rhyme, a decision that resulted in deadpan delivery of some seriously dark stuff, ratcheting up the humor in the process.

Subtitled Dark nursery rhymes to cheer you right up, if your idea of getting cheered up is somewhere along the lines of thugs getting beat-downs from senior citizens and people getting maimed consistent with the style of that scene from Fargo, you must buy this book, for one simple reason: it echoes the sentiments of subjugated Western society, providing a catharsis of schadenfreude.

Rosenfeld was born in Russia. He is a comic, so, go figure, he was depressed one day. To extricate Rosenfeld from his “funk,” as he called it, his dad, who immigrated from Russia when he was a boy, read him some traditional Russian nursery rhymes, which, in case you missed the lead, are dark, morbid micro-stories.

For some weak-minded serial killers, reading these would be preferable to the needle, gallows, firing squad, or Kim Kardashian lecture on how to identify your talent. For these timid takers of life, reading the nursery rhymes from Russian Optimism would either send their brains into shutdown mode, rendering them vegetables, or would convince them that humanity was on its way down the crapper anyway, no need for them to further it along with the application of their craft–i.e., killing people–so in true Russian Optimism style, they’d just go ahead and off themselves.

Death seems an appropriate ending to every nursery rhyme from Russian Optimism.

For non-serial-killer, Rosenfeld (not fact-checked, but reasonably assumed), depression led to the uncovering of the literary gem that is Russian Optimism. For the rest of us well-adjusted, non-serial-killer humans, we all get to enjoy the results of his cultural experience and translation skills juxtaposed with a deft handle on American appreciation for dark, sharp wit. Together with Smiley’s artistic mastery, they have woven together the equivalent of a studio audience laugh sign–it’s funny, you’re laughing, and you’re not sure why–if said sign were affixed to a tapestry, soaked in blood, crawling with vermin, and teeming with ravenous insects.

Death is funny. It just is.

Getting back to Peter (#2 in the Moral Messages chapter), maybe he was a mustachioed villain? Maybe the damsel’s man found out, hired Peter, so as to have a ready-made murder room, and strung him up with his own working materials? Was Peter the victim of a suicide? Really, really weird accident? Perhaps the kid is not a kid; maybe it’s a dwarf who is part of an S&M session, and Peter is secretly hoping the dwarf says the safe word soon?

I could conjure a thousand more questions for literary, Freudian, and legal analysis, but I think the intent of this Russian nursery rhyme isn’t hidden behind metaphor, making questions of intent pointless.

Why?

Because Peter’s dead, and it doesn’t matter.

Here’s why.

In America, we expect each successive generation to be richer, leaner, and have better hair than the previous–demand it, even. We believe if we paint ourselves into a corner, we will either get high off the oil-based paint or develop super-human abilities, levitate across the paint, and land safely on the carpet, or both, as the case may demand. Americans are eternal optimists.

Russians are eternal pessimists, but they don’t think of themselves as pessimists; they think of themselves as realists. Why get happy about anything when the rain clouds could appear at any moment, create a mudslide, and bury everything in sight?

Rosenfeld puts it this way in the book’s introduction: “Generally speaking, Americans expect each generation to accomplish more than the previous one. Russians expect each generation to suffer and be miserable. In reality, we all suffer the same, but Americans view suffering as a temporary setback whereas Russians see it as inevitable.”

These nursery rhymes reflect that way of thinking. It may seem absurd, but that’s the way they think. So rather than contorting our faces into aghast caricatures of Scream masks, I believe we can learn something from these snippets of Russian culture, these poison-pill nuggets of wisdom.

One final example to illustrate my point. Titled Happy Singers (ch: Cheery Children), the text says:

The children happily attend kindergarten,

The children happily sing.

Outside on the tree, carefully hang

A few children who poorly sang.

So sing loud and off-key if you want to, folks. Your life is pretty good, because as Ben Rosenfeld says in the introduction to the book, “These poems are a dark way of saying, ‘Don’t be so sad, things could be worse.'”